There are different practices for determining how a pastor serves a particular congregation.

There are different practices for determining how a pastor serves a particular congregation.The traditional method, used historically by the vast majority of Christians, has been appointment by a bishop. In other words, a man will serve in a ministerial capacity that his bishop (Greek: episkopos, lit. "overseer") has ordered. This is how the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican churches work to this day (as do many Lutheran churches around the world).

It's my understanding that the United Methodist Church (a spin-off of the Anglican church) operates this way, but has the added stipulation that a pastor not serve one specific congregation for more than a few years (seven?), that the pastors are periodically "rotated" at the discretion of the bishops.

A less traditional way of placing pastors puts the congregation as an assembly (instead of a bishop or other hierarch) in charge of the process. Thus, a council or a type of voting body within the congregation will issue a "call" to a pastor, and that pastor may then accept or decline this offer. This method is obviously favored by less hierarchical and more democratic (and congregational) polities. It is an inherently more American methodology.

My own church body, the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, though tilting in the traditionalist direction in many ways, calls and places pastors mainly along the latter (congregational) model using a "call process" (sometimes called the "divine call").

With the exception of a man's first call out of seminary (in which case the Council of Presidents, our equivalent of a council or synod of bishops, unilaterally places a man to serve as a pastor of a particular congregation or other ministerial capacity), congregations issue calls, and pastors either accept or decline them.

Of course, the process is surrounded in a pious appeal to the Holy Spirit, with a ritual of the pastor announcing that he is "prayerfully considering" a call - even though his wife may already be packing even while the pastor is announcing to his congregation and colleagues that he "covets their prayers" as he is "prayerfully considering this call."

And while the process is treated with the mystery of a papal election, some very practical matters really must be weighed: salary, housing, schools, proximity to family, type of congregation, etc. And yet, pastors do try very hard not to treat the process as a form of moving up to a better "job." Unlike in times past, these days there are often even interviews and sometimes flights to the potential congregation - thus turning the process more and more like a secular job interview. Sometimes salaries are even tacitly negotiated - which is not actually allowed.

Even apart from such abuses, I do think our current system has some flaws.

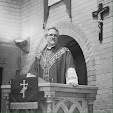

There was a time when a pastor's call was sacrosanct and treated like a marriage. For example, in Salem's parish hall (also known as Schmid Hall) - there is a portrait of the Rev. Eugene E. Schmid (1894-1967). He served Salem Lutheran Church right out of seminary from 1919 (at the age of 26) until his death in 1967 (at the age of 73). That's 47 years at this one parish. In the course of his ministry, he saw the roaring twenties, talking movies, the Model-T, the Great Depression, a World War (against the Germans at that), the breaking of the sound barrier, the post-war economic boom, the birth of television, the entrance of women in the work force, the Second Vatican Council, and the social upheaval of the sixties. Pastor Schmid continues to be revered and loved by the people here at Salem. Salem was his first and only call. In some cases, he baptized, confirmed, married, and buried people - and even their children. No matter how chaotic the world was becoming in the 1960s, there was Pastor Schmid preaching the same Gospel.

This was not that unusual in days gone by. In fact, many of the early church fathers interpreted Paul's instruction to Timothy that a pastor be the "husband of one wife" (1 Tim 3:2) as a reference to the relationship between pastor and congregation being like a marriage.

In many ways, pastoral ministry is like a marriage. Pastor and congregation do need to be compatible, they need to give-and-take in order to get along, they need to love and forgive each other. They need to be mutually faithful. The congregation, as a good wife, must yield to her husband's headship - provided, of course, that the husband is not abusive or ungodly. The Pastor is not to "lord over" his beloved (Matt 20:20-28), and his beloved is not to rebel against her God-given head (Heb 13:17). When a pastor is a faithful husband to his church (as our Lord Jesus is), and when the church is a faithful bride to her pastor, things go well. The wife is to be submissive, and the husband is to lay down his life for the wife (Eph 5:22-33).

But in this fallen world, things don't always go well. Pastors have to be removed. Parishioners have to be excommunicated. Pastors must be admonished, congregations must be called to repentance. Sometimes the relationship will no longer work. Sometimes a pastor's continued tenure would become so disruptive to the work of the Gospel that it is simply time to move on. Sometimes a congregation can't afford to pay a pastor enough to support his family, and it becomes time to find a different pastor that they can pay enough for his needs. Sometimes pastor and congregation separate with rancor, other times the split is amicable.

It can get complicated at times.

In the Missouri Synod, a pastor may opt to go on a "call list." Perhaps he is not being paid enough. Maybe he no longer fits in with his congregation. Maybe he is burned out. Perhaps it is time for him to move in a different direction in the Lord's kingdom. In such a case, he can announce that he is open to a call. He may get one, he may not. The district office has him on a list, and the district president (our rough equivalent of a bishop) may assist in the matchmaking process. Congregations are also free to issue calls apart from any district involvement at all.

Congregations can also appeal to the district president to get a pastor placed on a call list. Hopefully, they do this for legitimate reasons, and not merely out of rebellion or to settle personal scores.

In Pastor Schmid's case, he served Salem as his only ecclesiastical bride until his death. Pastor Schmid is my hero. I love my parish and my parishioners, and unless they reject me, or unless something supernatural calls me away, I see no reason to ever get a wandering eye. I would no more consider trading in my call here at Salem than I would consider trading in my wife. Obviously, if the church became unable to pay me, or if a hurricane should wipe us out (God forbid!), I may have to look at other options. But barring that, given my situation (which is not to speak for anyone else's) I believe it would be wrong for me to put myself on a call list or to consider a call somewhere else.

With all the talk of "healthy" congregations these days, I do think it is better spiritually for pastors and congregations alike to stay put. There is far too much of a "hire and fire" mentality among the congregations and far too much of a mercenary attitude among the pastors. There is not always a determination to work through problems, to lovingly do what needs to be done to make the relationship work. Of course, things don't always work out, but how often do people even try everything possible before throwing up their hands?

In the Missouri Synod, we have the situation where churches (often rural) who are small and don't have much money only have the option of calling a seminarian (due to the ability to pay him less than a more experienced pastor). In some cases, the seminarian is called to a double or even triple parish situation (serving two or three small congregations simultaneously). And in these cases, what often happens is that the young pastor in the ensuing years, marries, has children, and then can no longer afford to stay in that call. He goes on a call list, leaves, and is replaced by another seminarian. That's just a fact of life in many places. It is so uncommon for a pastor to remain in his original call for more than two or three (or maybe five) years that it has become common to refer to receiving one's "first call" out of seminary. It's a strange terminology. Can you imagine getting ready for your wedding, and then excitedly telling everyone about your upcoming marriage to your "first spouse"?

For the most part, the system works. Capitalism of a sort takes care of underpaid pastors as well as poorer congregations. But there is also a predatory nature of our system which I find problematic.

For example, a man may be happily serving a congregation. Maybe they aren't so big or so rich, but they are meeting the needs of their pastor. The pastor has no intention of leaving. But if he is a good pastor, his reputation will spread. Inevitably, even without his being on a call list, he will get a call from another congregation - probably a more "attractive" congregation in terms of money and prestige. The pastor is then given a dilemma: 1) Take a call that pays better money and gives him the opportunity to get out of debt, to provide for a better education for his family, perhaps even advance his education, and look to his own future, or 2) stay at this faithful parish that is paying him the best they can.

One of my colleagues was recently put into such a dilemma. He is the sole pastor of a small, but faithful parish that was founded not that long ago. The pastor and the congregation have a good, scriptural relationship. He was not on any call list. However, out of the blue, a call came from out of state to a very old, established, prestigious, and wealthy congregation - one with great visibility to one of the church's seminaries, with very important and influential members - both lay and clergy.

He would have been an associate pastor at this imposing congregation. His salary would likely have skyrocketed (though I don't know this for a fact). This congregation already has a solid senior pastor, and they were seeking a second pastor, and in the process, were willing to deprive a smaller, not as wealthy, less prestigious parish of her only pastor.

The process strikes me as unchristian, as predatory. It puts pastors into being tempted by money and prestige. It reminds me of Nathan's example to King David about a rich man who had many sheep conniving to deprive another man of his one and only beloved ewe (2 Sam 12:1-6). Of course, luring a pastor away from his congregation is more a case of "shepherd stealing" than "sheep stealing" - especially considering that the word "pastor" is Latin for a "herder of sheep."

In the example I'm thinking about (that is, my friend who was given a call to a prestigious church), I'm pleased to report that he turned down the call, and opted to stay put. This speaks volumes about my colleague's character and devotion to the parish the Lord gave him to serve.

Personally, I think it should be forbidden for a congregation to issue a call to any man who is not on a call list. Maybe we should treat our "first calls" as our "first wives" - and commit to them, pastor and congregation alike, "until death us do part" - unless there are real issues (whether unresolvable conflict or salary) that would make a "divorce" necessary. As it stands now, there is an unspoken understanding that a man's "first call" is temporary, and that if he is a good pastor, another congregation will "put the moves on" him and lure him away from his current call. Perhaps it should be as off limits to woo a pastor who is not on a call list as it is to seek to lure a person who is wearing a wedding ring into marital unfaithfulness.

I'm sure my view is a minority view, and that this situation will not be changed in the Missouri Synod. I'm also sure many will argue that such predatory calls are the work of the Holy Spirit, and thus should be permitted. It can be argued that allowing these kinds of calls ultimately raises the pay and standard of living for pastors, and gives congregations a "supply and demand" incentive not to be stingy. But I still find the process distasteful and neither in the interest of pastors, laymen, nor the work of the Gospel. I have no evidence to support my opinion, but I honestly believe serial pastors are as desirable in the parish as serial marriages are in the family. I also believe the stability of a consistent parish pastor in the lives of the congregants is akin to the continued presence of a family's father in the lives of the household.

Every day, I walk past Pastor Schmid's portrait. Although we Lutherans don't pray to saints, I have to confess, I can't help but give my predecessor a respectful nod and a warm greeting when I stroll by. I have heard "Pastor Schmid stories" for as long as I have been here. Pastor Schmid could be strict and harsh, but also tender and kind. He knew his people, loved them, served them tirelessly and selflessly, and stuck with them even through terrible trials. He stood manfully at his post until the Lord called him to Himself. I never met the man, but there is a bond between us that transcends this earthly life. He is part of the "angels and archangels and all the company of heaven" with whom we worship the Triune God in our sanctuary. It is my privilege to take my place in the same pulpit and at the same altar where Eugene Schmid ministered for nearly half a century.

21 comments:

The longest serving pastor at my previous congregation served 20.5 years. He took the Call when he was 63 years old, after taking 13 years off to tend to his sick wife who finally fell asleep in Jesus. He was reported saying he'd take the first Call that came his way. The good people at Trinity called him. He stayed until he was physically unable to perform the duties of the Ministry. Even then, he wanted to stick around. His son had to talk him into resigning.

A couple of years after he came to Trinity, the largest congregation in the district (now the 2nd or 3rd largest) called him as associate pastor. Most everyone thought he would take the Call and move on, as many pastors before and since have done.

The pastor declined the Call and stayed put. I'm sure it was a shock to everyone at Trinity.

His reason for returning the Call? The big congregation can call anyone they want. Trinity would have a difficult time finding another pastor. They would probably ask for a seminary graduate. It was best for both congregation that he stay put and let the big congregation call someone else.

The story made the district Lutheran Witness insert. The pastor was lauded in heroic words.

I wonder if such a thing happened today if the pastor would have his sanity called into question?

He did the right thing. So did the pastor you mentioned in your post.

Thanks for the great post!

I think there is only one call, and that is into the holy ministry of the church. The other "calls" really are more akin to placements or assignments. A good analogy would be entering into the military. You may serve at any number of bases, but you're always part of the army. The congregation is not so much the wife, as is the church. Thus, I do not think it is wrong in any way to consider a "call" to another congregation. (Admittedly, this is simpler in an episcopal system, where the bishop says, "Go," and you go.The idea that the Lord is "calling" a pastor to two places, i.e., to the one he is serving at present and to another place seems non-sensical.) If the church determines that a person is better fitted to serve a different congregation, he should, by all means, go. As one serves, one develops certain skills which the church recognize are needed elsewhere. For instance, Paul knew the Corininthians needed Timothy and sent him there to clean things up. A person serving in a smaller church may be ready to handle more responsibility, or an older pastor may be ready to shepherd a smaller flock. The possibilities are many. Admittedly, this is more difficult to put into practice in a congregational system, but the ideal is still to be strived for.

Peter:

This is a great point you make about the military analogy. Like the children's song we sang in the Baptist Church ("I may never fight with the infantry (etc.), but I'm in the Lord's Army"). The episcopal system mirrors the military model better, for in our system, a call is not so much an "order to be obeyed" as it is a "request to be considered" that may ultimately be obeyed (treated as a lawful order) or disregarded (treated as an unlawful order).

Which begs the question, if an LCMS call can be disregarded, is it *really* the work of the Holy Spirit? Does the Holy Spirit issue invalid orders? Obviously, some of our calls are valid orders from the Holy Spirit, but if we discern that a call should be turned down, then did the Holy Spirit ever actually issue a call through the other church's voter's assembly? It would seem to invalidate the process.

And if a man can be issued a call independent of his status as being on a call list or not, then what is the purpose of the call list? It seems like a charade.

Unlike the example of Paul giving Timothy orders, there really is no authority or oversight (episkope) being exercised in our system (first calls excepted).

So, what (if anything) should be done about what I called the "predatory" call? It just seems inherently wrong to me for a wealthy church that already has a pastor to try to woo away a pastor from a weaker church that has only one pastor. If the Church is truly *one*, holy, catholic, and apostolic; if we are truly *one* body; it doesn't follow that one member of the body should play "cut-throat" with another member. Should the arm benefit at the expense of the leg?

What am I missing here?

Fr Hollywood,

Great post. I couldn't agree more.

Your position on this matter has the support of the ecumenical canons. Canon XV of the first council of Nicaea reads as follows:

On account of the great disturbance and discords that occur, it is decreed that the custom prevailing in certain places contrary to the Canon, must wholly be done away; so that neither bishop, presbyter, nor deacon shall pass from city to city. And if any one, after this decree of the holy and great Synod, shall attempt any such thing, or continue in any such course, his proceedings shall be utterly void, and he shall be restored to the Church for which he was ordained bishop or presbyter.

And the Nicene canon is a strengthening of an even earlier canon, number XIV of the so-called "Apostolic Canons":

A bishop is not to be allowed to leave his own parish, and pass over into another, although he may be pressed by many to do so, unless there be some proper cause constraining him, as if he can confer some greater benefit upon the persons of that place in the word of godliness. And this must be done not of his own accord, but by the judgment of many bishops, and at their earnest exhortation.

First off, I wouldn't be too quick to label a call "predatory." In the example you mention, I think the pastor made the best, and most churchly decision. Still,it might just be the case that the larger church is precisely the place where a skilled pastor, having gained some experience in a smaller parish, needs to be. This isn't necessarily predatory, it is a good use of resources and manpower. Bishops make such "predatory" decisions all the time, for the sake of the church at large.

In another case, a pastor overwhelmed by the demands of a larger congregation, may need to be advised by the church to go to a smaller place more suited to him. Of course, it's not just a matter of size. We want to put certain talented people in challenging and struggling places. Sometimes, the church might want to place a fellow in a strange place in order to "stretch" the man, and to develop him for greater service in the kingdom. The thing is, I think, is we need to consider ourselves a church, and not simply a conglomeration of congregations. We really are all in this together. I have no easy answers. In some ways, I think, we would do well to be paid by the church at large and not the congregation, though there would be advantages and disadvantages to about any scenerio. And, admittedly, this is easier, I suppose, in the Catholic church, where all the men are unmarried, and much more portable. But that is more a matter of logistics than theology.

As for the "call process," I think we should put it into perspective. Again, there is but one call, into the Ministry. The rest is simply using the best of our discernment to place men where they can best serve. This is a matter of judgement, which, admittedly may be made more difficult by our congregational system. Surely, it places more onus on the pastor, who must ask himself where he can best be of service. In this process, I think, it's a good idea to consult one's brothers in the ministry on such matters, for they often have a better sense of our own talents and shortcomings than we do. It can be the case that pastors will profess allegiance to their own congregations simply because leaving, to go to another place, does not fit into their own personal preferences. Such pastors may be afraid to move, and may need a friendly kick in the rear to get them to go where the church at large really needs them.

Pastor Beane, thank you for this article. This is great.

I can see the objection of a congregation's calling for an assistant pastor at the cost of another congregation's single pastor. Do you think the reverse is also objectionable, an assistant being called to be a sole pastor, if the assistant is not on a call list?

Peter:

I see what you're saying, but in practice (at least in a congregational system), it typically means that small parishes - especially rural ones - are going to have many pastors with short tenures, whereas richer parishes (usually larger and/or more prestigious) will have the luxury of few pastors with long tenures. And this is not determined by what's best for the church at large, but rather to a great extent by economics. If we had bishops, those decisions could be made apart from market forces.

To use my own parish again as an example, it was never a large or influential church, but Schmid, like many pastors in his day, stayed here for decades. He gave the parish a sense of continuity.

But this has changed. It is much more rare for a pastor to remain in one call (or assignment, if you will) for a long period. Is this because it is better for the church at large that men move around more?

I just don't see this as a good development for the church at large. Maybe I'm all wet on this, but I think the current culture of "first calls" and "hop, skip, and jump" to be of inferior service to parishioners and to the Gospel than men who are willing (and encouraged by a churchly culture of longevity) to stay put for long periods of time.

We certainly don't encourage parishioners to jump around from church to church, and we frown on "sheep stealing," why is it encouraged for pastors to jump around? Shouldn't it equally follow that a parishioner may need to be "stretched" by leaving a small parish for a larger one, or that a church member may be better equipped to serve as a lay leader at Church A instead of Church B?

I see you concerns, Father Hollywood. My own grandfather served the same congregation during his entire ministry, and this was indeed a blessing. And, I would never encourage a pastor to "jump around." However, I would encourage a pastor to move if the church needs him elsewhere. I imagine that Bishops have to make painful decisions all the time. Whenever they move good men from smaller congregations, it can't be easy.

But indeed, I have seen pastors unwilling to move, simply because they don't want to have to face a new challenge. It's much easier to "stay put," especially when you like your life the way it is.

In the best of worlds, a change might mean moving to a bigger, or a smaller church. Or to a church that's in turmoil, and needs a steadying hand. Or to a church that's grown complacent, and needs to be shaken up. Again, the possibilities are endless.

Strangely, you are perhaps more "congregational" in your thinking than I. The fact that there is abuse, I have acknowledged (hence, my suggestion that we all be paid the same, or according to an army-like scale).

As for your comparison between a pastor and congregational member being "stretched," I don't see it.

It's in the very nature of a pastor to be "sent," and to go wherever the Lord wills. James and John will follow our Lord to many different places. Their father Zebedee is free to stay where he is in the fishing boat.

The church may, for instance, see you as a potent preacher, and suggest you become a missionary. Or they may see you as a good teacher, and send you to a seminary. Perhaps, you have a lively mind, and would be perfect for ministry in a college town. Perhaps, you are getting stale, and need to be shaken up. In any case, the question to ask is where you can be of best service.

And here, please note, I am not talking about all the bad things that can happen in the church. I am saying that this is how a faithful pastor should consider his call. Yes, there is abuse in moving towards more money. We should guard ourselves against that. However, we should also be open to serve where the church needs us, wherever that may be. In other words, let's not worry about the decisions of others. Let's think about how we are going to make good and Godly decisions, according to what's best for the chruch.

(Btw, I've probably said too much. So pardon my many words.)

Peter:

Don't apologize for using many words - it's nice to engage in a stimulating conversation!

Dan:

I guess I wouldn't find it as bad, but I still think it would be best for congregations not to call a man unless he is on a call list. From my conversation with Peter, it kind of looks like in our LCMS culture, a pastor is *always* on a call list whether he is on a call list or not.

I'm still trying to wrap my head around that.

Yes, I agree we are always on a call list, to use that phrase. Just as a soldier is always available and ready to serve whereever in the war he is needed.

One other thing. I can think of many good reasons why a man ought to consider a call to a smaller congregation. In a smaller congregation, you can study more, and meditate more on the Word. And, also write more. The church could use learned pastors in small congregations to write more of their Bible-study, and Sunday-school materials, for instance. Men in smaller congregations might also do well in the role of circuit counselor, because they have more time to help their brother pastors in need. Indeed, in the age of the computer, there are probably many more ways that a pastor of a small congregation can use his talents for the church at large.

Peter:

I appreciate your example of Zebadee, but people do transfer to and from congregations for a number of reasons. In general, we encourage people not to do that. I realize the office of layman is different than the office of presbyter, but I still can't help but see luring pastors away from their sheep as somehow analogous to luring sheep away from their shepherds. "What God has put together" and all that.

Unlike Pastor Schmid and his generation, we live in a social context that worships change, is impatient, and has a short attention span. We are less rooted and more mercenary than our forbears (we have smaller families today, but seem to "need" bigger houses and more money).

I fully acknowledge there may well be good reasons for a change in pastoral oversight over a parish, but on the whole, I think we're way too "jumpy." I think the church was better served when the average time at a parish was longer, when a "first call" was not seen as a necessary temporary hoop to jump through. I have no evidence for my suspicions, though, and I may be totally off the wall.

But I still think it is like 2 Samuel 12 for a wealthy congregation to dangle a call (for a second pastor, at that) under the nose of a sole pastor, who isn't on a call list, who serves a congregation that simply can't compete in terms of salary, etc. It just seems cruel, both to pastor and flock.

Maybe I'm being overly parochial or provincial about it, but it just seems wrong to me. I know it does lead to a sense of fatalism when a rural or remote parish gets a really sharp guy right out of the seminary. Parishioners in that situation feel like it's only a matter of time before their pastor ditches them for something more "attractive." Love shouldn't work that way.

Maybe Schmid had the abilities to aspire to be a DP, or a foreign missionary, or even a seminary professor (I really don't know if he had those talents or not). But whatever gifts he had, he stayed here in Gretna and served as a parish priest to the same folks for 48 years. I just think more of that kind of thing would be better, not worse.

Then again, I may have a distorted view because of my congregation's own history.

God bless Pastor Schmid, and my own dear Grandfather. There is something good, right, and salutary in staying in the same congregation. And, I agree that the main temptation today is money. Still, do not discount the temptation of complacency. If you receive a call, it will be hard to leave New Orleans, simply because it's such a wonderful city, and your family likes it. And then there's sentiment. And also the idea that the congregation wouldn't be able to get along without me. There are many factors that come into play.

And, I agree we should encourage loyalty, and the deepening of relationships.

But, if it were the case that you were called to a place that needed you more, then you should go. And that might mean leaving a big church to go to a mission church in the inner city. Or taking a pay cut. Or, even going to a suburban church that could really use a confessional pastor!

In any case, I think the best thing to do is to talk to your brothers in the ministry. They'll often be able to see the situation better than you, simply because they have the perspective of distance.

I should also add, leaving your congregation may not be an act of disloyalty. If you were called, say, to a mission in Kenya (ok, I'm tugging at the heart-strings), my guess is that no one would begrudge you. In fact, you would go with your congregation's best wishes and prayers, for their desire is the same as yours. That the gospel be preached, and that our Lord's kingdom may come.

It seems that we should consider Luther's teachings on the tenth commandment here. If a Pastor is faithfully serving a church, why would another church wish to deprive them of their Pastor? Hmmm, could it be - covetousness?

Chad's point is based on congregationalism. It's not that another congregation "covets" a pastor, it's that the church recognizes the fact that a given pastor has talents that would be helpful in another situation.

Chris:

Thanks for those citations! Interesting.

Peter:

I don't know if it's fair to brush away criticism of our current system with the epithet "congregationalism." Our polity is congregational, and we have no episcopal authority to oversee the allocation of resources - human and otherwise - in our synod.

I wonder if our current method of receiving a call and either accepting it or rejecting is is a form of "receptionism" - insofar as if you accept it, it is a "divne call," but if you reject it, it somehow isn't. That makes its divinity dependent on its "reception."

I do think you make an excellent point about the church's need for men with extraordinary talents. I know some of my classmates are outstanding scholars - one is translating and editing additional volumes to Luther's Works, others will, no doubt, teach at seminary. The church does need to tap their resources.

So, how does the church go about recruiting such men? Lacking bishops, we need to find another way. However, the church had the same extraordinary needs in Pastor Schmid's day - and yet, it was not uncommon to find parish pastors serving in the same place for decades. What has changed? Not the needs of the church, surely.

And I'm still confused by the concept of the "call list." Do they exist or not? I do think that if a pastor has come to the conclusion that it is time to move on, he can submit his name, and see what happens. If a young pastor is told by his peers that he should consider a call to CPH or the seminary, he should place his name on a call list, and let his congregation know. But for one parish to contact a pastor out of the blue - when he is not on a call list at all - just sounds like seduction. And when there is a great inequality of wealth or prestige, it just seems predatory.

What is wrong with a pastor opting to place his name on a call list if he believes (or is convinced) that it is time for a change, and only limit potential calls to men on that list? That would allow the parish to be aware of the situation, and would allow a pastor to be prepared for receiving a call. It seems like a better way for congregations to be in harmony with each other in the one body of Christ, rather than pitting one member against another.

Is this unreasonable?

I definitely understand the need for a "call list." All I wanted to say was that we are all available for a change in position, depending on our church's need. Frankly, I am very "closed" to a call, because I think I am where I belong. But, I could be wrong.

This is a bit late in coming, but I just read your post on Pastor Schmid. To tell you the truth, it made me cry. Yep. It made my dad tear up, too. You see, Pastor Schmid was my grandfather and my dad's dad. Thank you for your honoring of him. I didn't know him well since he died when I was very young. I do appreciate your perspective. One of these days, I'd like to make a trip to Gretna. The last time I was there was when Grandmother Schmid died and I was pretty young at that time, too.

Over the years, I've prayed for the congregation at Salem and am glad to see they have a pastor who is commited to them and the Word of God.

Could you send me a brief history of Salem school?

Dear Susan:

Thanks for your kind words! Pastor Schmid was a noble man and a saintly pastor. He is still fondly remembered here. I hope you will come and visit us some time!

I don't know that there is a written history of our school. Let me see what I can find.

Post a Comment